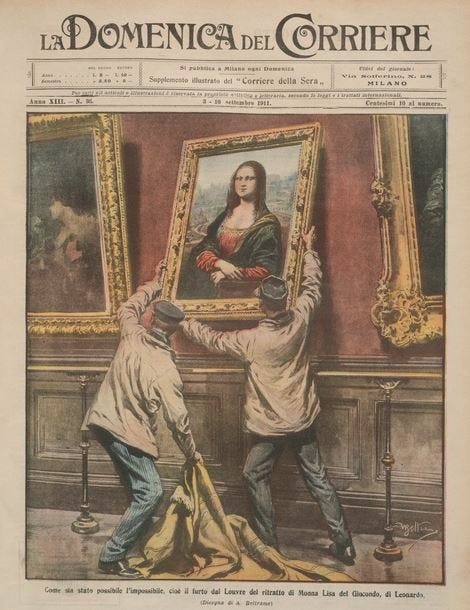

On the morning of August 22, 1911, the Louvre woke up to a problem: the Mona Lisa was gone. In its place were four iron hooks and a mountain of questions. The theft carried out with astonishing simplicity, exposed the museum's more-than-relaxed security.

Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian handyman and former Louvre employee, entered the museum on Monday morning wearing a plain white worker's smock. The building was closed to the public, but that hardly mattered, he looked like he belonged. With confident steps, he headed to the Salon Carré, unhooked the painting, and disappeared into a service stairway. There, he carefully removed the Mona Lisa from its frame and hid it under his coat.

He didn’t leave right away. He waited for hours, possibly even until the next day, taking advantage of the museum’s closure to slip away unnoticed. When he finally walked out with the painting under his arm, no one stopped him. No one even noticed.

Chaos erupted the next day. The Louvre shut its doors, and Paris police questioned everyone—guards, restorers, even avant-garde artists. Guillaume Apollinaire and Pablo Picasso were dragged in for questioning, victims of an investigation more imaginative than effective.

Meanwhile, Peruggia kept the painting hidden in a trunk, just a short walk from the Louvre. For two years, while newspapers speculated and detectives chased false leads, the Mona Lisa sat quietly in a modest apartment on rue de l'Hôpital Saint-Louis. Peruggia claimed he acted out of patriotism, convinced the painting belonged in Italy. Sincere belief or last-minute excuse?

In December 1913, Peruggia contacted a Florentine art dealer, Alfredo Geri, offering to "return" the Mona Lisa to Italy. Geri, suspicious, brought in the director of the Uffizi Gallery. They authenticated the painting and called the police. On December 12, 1913, Peruggia was arrested in a Florence hotel.

His sentence was light. The judges found his patriotic reasoning more charming than criminal. In the end, he accomplished what centuries of critics had not: turning the Mona Lisa from a masterpiece into a pop phenomenon.

Today, the crowds pressing forward to snap photos of the Mona Lisa owe as much to Leonardo as to an Italian handyman with a clumsy plan.

I can’t help but imagine Leonardo having a good laugh at this.

Sergey Meniailenko from Cupertino, USA, Visitors of Louvre in front of Mona Lisa, CC BY 2.0

Stealing a Leonardo is no small feat, yet history records more than one attempt. The 1911 disappearance of the Mona Lisa is the most famous, but another case (this time involving a portrait of Isabella d’Este) raised questions of its own.

Initially suspected to be a theft, its story turned out to be far more complex.

Read more here:

In fact Peruggia had planned a get rich scheme from the beginning. I wrote two stories about this!

We've used this wonderful text to practice English reading skills at my Uni —thanks a lot for this and God bless you.