The Expert Commission

Berlin, 1904: when circus directors sat alongside scientists to judge a horse's intelligence

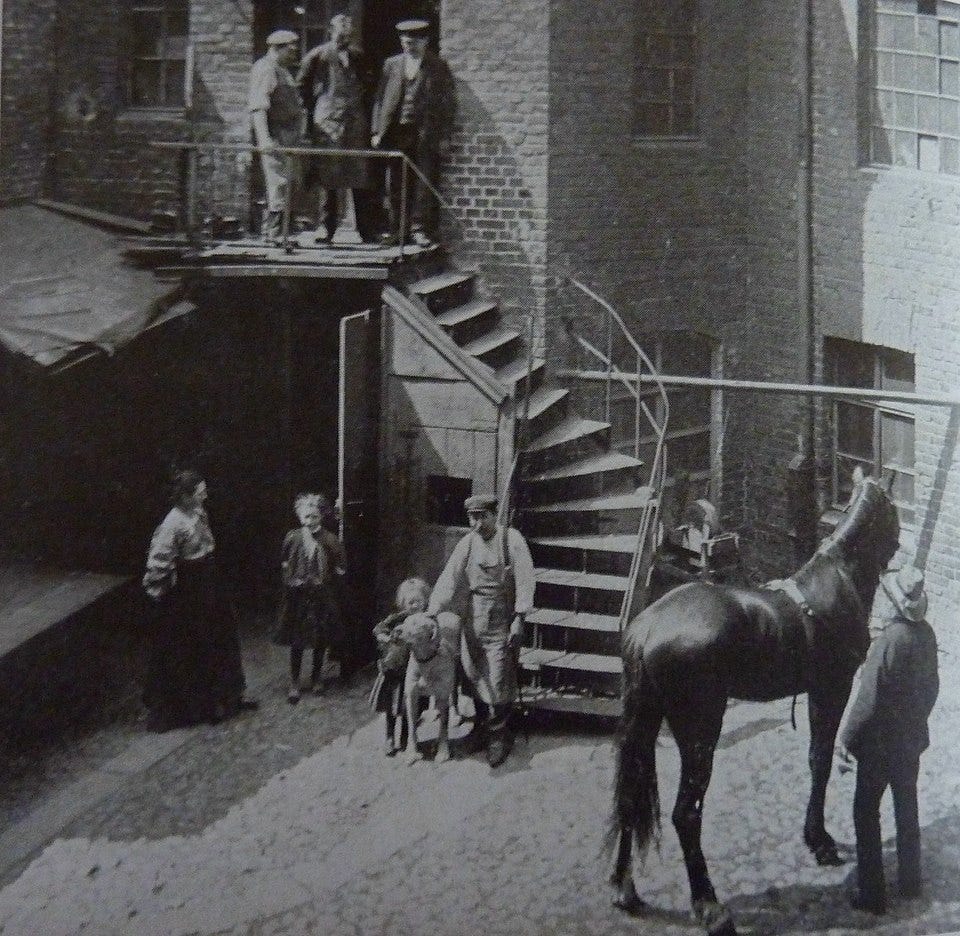

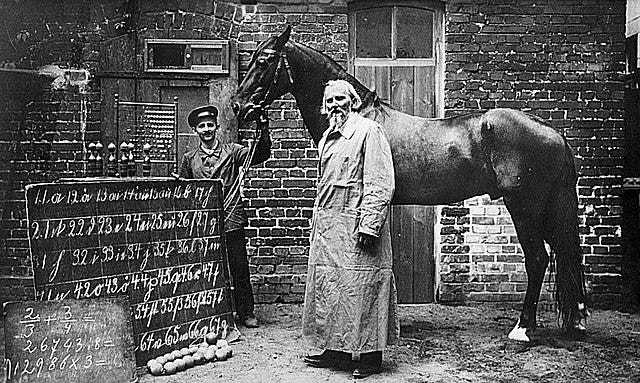

Wilhelm von Osten arranged his teaching materials with methodical precision in a courtyard of Griebenowstraße. Large wooden skittles, a makeshift abacus, brass numbers hanging from a cord.

The former gymnasium mathematics teacher had also studied phrenology—the measurement of skull bumps to divine character traits—and was considered something of a mystic. In his systematic mind, the boundaries between pedagogy, pseudoscience, and genuine discovery remained fluid.

The Era of Thinking Animals

This was Berlin in 1904, when the distinction between entertainment and inquiry had not yet hardened into modern categories.

The capital teemed with what the era called "thinking animals", whose performances promised to both marvel and instruct.

These spectacles reflected the era's fusion of scientific optimism and visual pedagogy, when knowledge was transmitted through demonstrations, magic lantern shows, and participatory experiences that engaged public curiosity.

Von Osten's Hans was hardly unique. There was Rosa, a mare who performed in a Berlin vaudeville theater; traveling menageries whose exotic animals seemed to respond to complex commands; circus elephants that appeared to understand human language.

The phenomenon extended across Europe, a "school" of animal intelligence that would persist from the late nineteenth century into the 1950s, sustained by the era's faith in the educative power of spectacle.

These exhibitions served multiple cultural functions simultaneously. They satisfied the period's craving for visual, participatory science and appeared to demonstrate humanity's rational mastery over nature through systematic training.

The careful instruction of animals became a metaphor for civilization itself, proof that the methodical application of human intelligence could transform the seemingly impossible into a routine accomplishment.

The Mathematical Horse

Von Osten's student was a nine-year-old stallion named Hans, and by September their partnership had attracted crowds to the narrow courtyard.

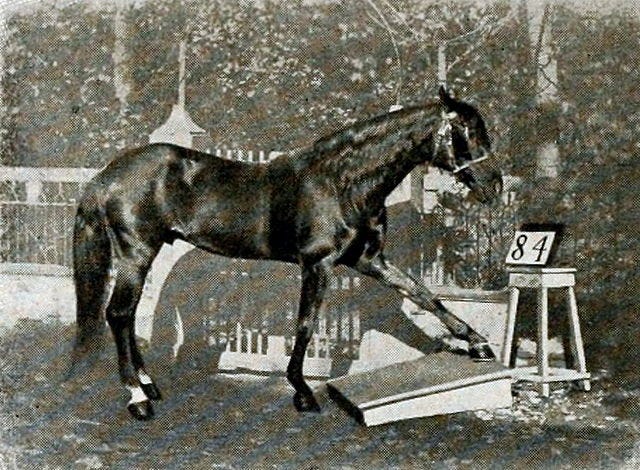

Hans could add, subtract, multiply, divide. He could spell words by tapping his hoof according to each letter's alphabetical position. When presented with colored rags, Hans would strike the ground the correct number of times to indicate blue, red, or yellow.

The method was entirely orthodox: the same pedagogical principles von Osten had applied to human pupils for decades.

But Hans represented something different from the typical performing animal. Von Osten exhibited no showmanship, employed no obvious tricks. This was presented as pure education, an extension of the classroom to include a species previously considered incapable of conceptual learning.

The distinction mattered to contemporary observers, who had grown accustomed to circus animals performing elaborate routines but had rarely encountered what appeared to be genuine intellectual development.

Scientific Intervention

The controversy that erupted revealed the intellectual anxieties of Wilhelmine Germany. As zoology and physiology established themselves as autonomous disciplines, questions about animal intelligence had gained scientific legitimacy.

Darwin's work had already unsettled traditional hierarchies between human and animal cognition. Von Osten's systematic approach, employing standard educational techniques rather than entertainment training, seemed to offer empirical evidence for animal reasoning abilities.

Berlin's Board of Education felt compelled to intervene, appointing a commission of experts that became known as the "Hans Commission”, whose mandate was to determine whether Hans's performances involved fraud or trickery.

The composition of this group illuminated the uncertain boundaries between legitimate and illegitimate knowledge in the early twentieth century.

Alongside representatives of science appeared military officers, school principals, and a circus director who had initially declared himself "extremely skeptical about the matter," believing Hans had simply learned "a few clever tricks just like other well-known circus horses."

Here was the fundamental question: who qualified as an expert in evaluating animal intelligence?

The commission's mixture of academic authority, military discipline, and entertainment industry knowledge reflected a moment when such expertise remained undefined.

Busch's presence acknowledged that circuses, not universities, had developed the most sophisticated understanding of what animals could actually be trained to do.

The Investigation

The commission's examination proceeded with Germanic thoroughness. Hans performed arithmetic, answered questions about colors, identified musical notes when converted to numerical values. He responded correctly even when von Osten was absent, accepting questions from commission members with apparent equanimity.

The investigators found no evidence of deliberate fraud.

Their cautious report admitted that Hans's performances could not be attributed to conventional training methods. There was, they concluded, no detected "trick" in the accepted sense. But the document's careful language left room for unknown mechanisms.

Carl Stumpf assigned his colleague Oskar Pfungst to conduct more rigorous testing.

Pfungst's investigations introduced experimental controls that would become standard in psychological research: isolating Hans from spectators, using multiple questioners, ensuring the horse could not see his interrogator, and crucially, conducting tests where neither horse nor questioner knew the correct answer.

This final condition proved decisive. When deprived of visual contact with questioners who knew the answers, Hans's mathematical abilities vanished.

Pfungst's meticulous observations revealed the mechanism: unconscious postural changes, pupil dilation, breathing patterns—involuntary signals that questioners transmitted without awareness.

The Clever Hans Effect

Von Osten had been genuinely convinced of his student's intelligence. His signals were entirely involuntary, his faith in Hans's abilities completely sincere.

The discovery's implications extended beyond one horse's abilities. Pfungst had identified what would become known as the "Clever Hans effect"—the influence of unconscious expectations on experimental subjects.

Pfungst's discovery had lasting impact on experimental psychology. The Hans case provided an example of rigorous methodology applied to extraordinary claims. Phrenologists claimed to read character from skull measurements, mesmerists demonstrated seemingly inexplicable mental influences, yet Pfungst's investigation remained methodical and controlled.

It showed how unconscious communication could masquerade as cognitive ability, even when all parties acted in complete sincerity.

After the Discovery

Von Osten never accepted Pfungst's explanation. Despite the scientific findings, the elderly teacher continued exhibiting Hans throughout Germany, attracting enthusiastic crowds who remained convinced of the horse's abilities.

Von Osten died in June 1909 and Hans was then passed to Karl Krall, a jeweler from Elberfeld who remained convinced of equine reasoning abilities despite Pfungst's findings. Krall continued the experiments, eventually acquiring two additional horses to create what became known as "the famous horses of Elberfeld."

Hans continued performing under Krall's direction, but his cooperation had diminished. In 1914, when Europe mobilized for war, Hans likely followed the fate of countless horses conscripted for military service.

After 1916, all records of Hans disappear.

Unverified accounts claim hungry soldiers consumed him: a rumor that, whether accurate or not, marks the distance between von Osten's courtyard in 1904 and the trenches a decade later.

What remained of the whole Hans story was a new understanding of the subtle communications that flow between species, and the recognition that intelligence itself might be less transparent than the Belle Époque had presumed.

Well, Hans could have given some humans a run for their money. What a fascinating story!