On February 7, 1897, Le Figaro published a brief notice on its front page:

A pistol duel took place yesterday in the outskirts of Paris between Messrs. Marcel Proust and Jean Lorrain, following an article published by the latter under the signature Raitif de La Bretonne.

Two bullets were exchanged without result.

The witnesses for Mr. Marcel Proust were Messrs. Gustave de Borda and Jean Béraud; those for Mr. Jean Lorrain were Messrs. Octave Uzanne and Paul Adam.

Behind that dry chronicle lay something unexpected. Marcel Proust, twenty-five years old, a chronic asthmatic and writer of delicate manners, had challenged one of Paris's most feared journalists to a duel.

The article that had triggered it all had appeared in Le Journal on February 5, signed with the eighteenth-century pseudonym that Jean Lorrain liked to use for his most ferocious attacks.

Under that libertine mask, he had demolished "Les Plaisirs et les Jours," Proust's first collection published the previous year.

But he had not stopped at literary criticism. He had added personal insinuations, venomous allusions about salon habitués, and veiled accusations of homosexuality.

(…) Mr. Marcel Proust nonetheless managed to get a preface by Mr. Anatole France, who had never written one for Mr. Marcel Schwob, Mr. Pierre Louys, or Mr. Maurice Barrès.

But such is the way of the world, and rest assured: for his next volume, Mr. Marcel Proust will secure a preface from Mr. Alphonse Daudet, the unyielding Mr. Alphonse Daudet himself, who will be unable to refuse it, not to Madame Lemaire nor to his son Lucien.

Lorrain's insinuation was cutting and precise.

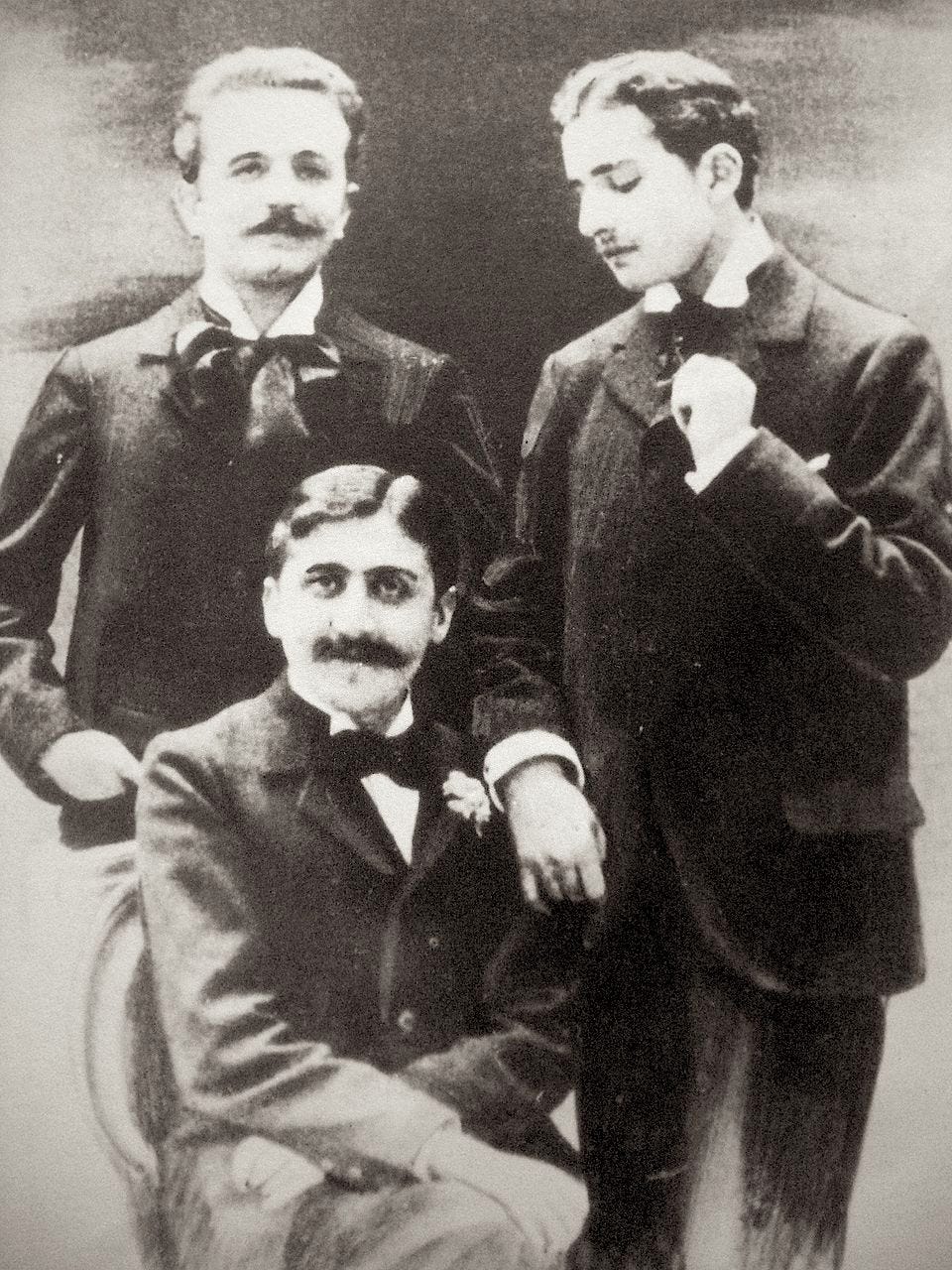

Madeleine Lemaire was a celebrated salon hostess and watercolor painter who had illustrated Proust's book, while Lucien Daudet was the eighteen-year-old son of the famous novelist and Proust's close friend.

Marcel Proust (seated), Robert de Flers (left) and Lucien Daudet (right), ca. 1894 in a photo by Otto Wegener.

The subtext was clear: it was not merit, but connections, that explained certain literary endorsements.

In 1897, those words still demanded a response with weapons. The bourgeois code of honor was rigid: an insulted gentleman had to seek satisfaction, or else lose his social reputation. Proust knew this, and he also knew that backing down meant admitting to the accusations.

At the time, dueling was formally illegal in France but socially tolerated, especially in literary circles where a printed polemic could easily become a matter of honor.

It was not about seeking the adversary's death, but about staging one's courage: a codified theater where the objective was to prove one could uphold one's words even in the face of danger.

The choice of witnesses reveals much about the world in which the young writer moved. For Proust: Gustave de Borda (a fencing master) and Jean Béraud, the celebrated painter of Parisian life. For Lorrain: Octave Uzanne, a refined bibliophile, and Paul Adam, a novelist in vogue.

This was no street affair: it was business between people who mattered, in the literary and artistic microcosm of the capital.

The details of the encounter are recounted by Le Figaro with the bureaucratic precision of the era: two shots fired, no one wounded. Honor restored according to the rules.

Youthful rashness or perfect adherence to the code? Perhaps Proust, on February 6th, 1897, had simply done what every gentleman was expected to do.